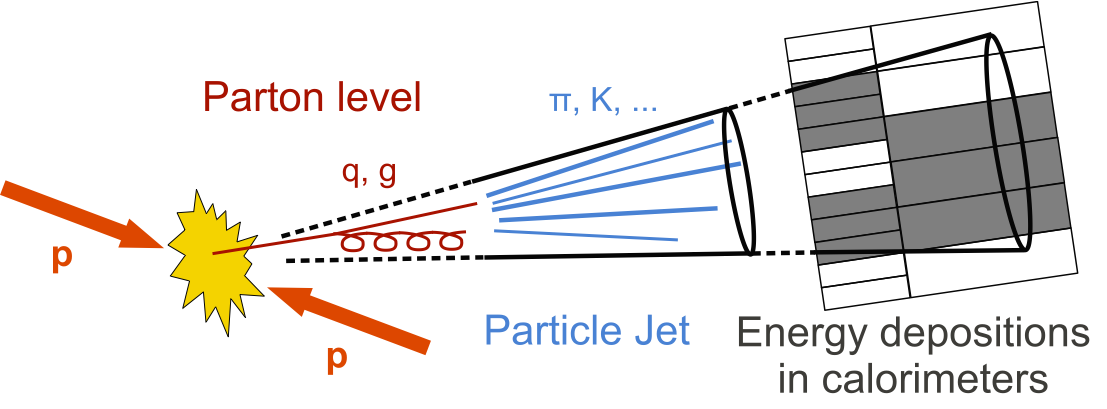

Jets are the experimental signatures of quarks and gluons produced in high-energy processes such as head-on proton-proton collisions. As quarks and gluons have a net colour charge and cannot exist freely due to colour-confinement, they are not directly observed in Nature. Instead, they come together to form colour-neutral hadrons, a process called hadronisation that leads to a collimated spray of hadrons called a jet.

As these jets of particles propagate through the CMS detector, they leave signals in components such as the tracker and the electromagnetic and hadronic calorimeters. These signals are combined using jet algorithms to form a reconstructed jet. However, the energy of the reconstructed jets does not correspond to the true particle-level energy, which is independent of detector response. The jet energy corrections relate these two values; the detailed understanding of the jet energy scale is of crucial importance for many physics analyses, and it is often an important component of their systematic uncertainty.

Within CMS, three different methods to reconstruct jets are supported with jet energy corrections: a calorimeter-based approach; the “Jet-Plus-Track” approach, which improves the measurement of calorimeter jets by exploiting the associated tracks; and the “Particle Flow” approach, which attempts to reconstruct individually each particle in the event, prior to the jet clustering, based on information from all relevant sub-detectors. The significantly improved resulting jet energy resolutions, especially at low transverse momentum (pT), indicate that the “Particle Flow” approach offers advantages with respect to the other types. Indeed, it is used by most physics analyses within CMS.

CMS follows a factorised approach to jet energy corrections. At first, the additional energy in the event induced by overlaid low-energy proton-proton collisions (pile-up) is subtracted. For one high-energy head-on proton-proton collision, there are in 2012 – on average – more than 20 of such additional collisions taking place at the same time.

Secondly, to compensate for the non-linear response of the calorimeters (as a function of pT) and variations of the response in pseudo-rapidity (η), corrections are determined from simulations. These corrections are cross-checked using data-driven methods: Currently, there are analyses determining the relative scale as a function of η from di-jet events and the absolute scale in the central detector region (|η| <1.3) from Z+jet and γ+jet events.

These analyses show that the previous calibration steps are working as expected and only minor differences in the jet energy scale between simulation and data are observed. As depicted in Figure 2, these differences are of the order of 1% in the central detector region and below 5% in the region up to |η| <2.5. However, these small remaining differences are explicitly corrected for in data in the residual correction step, which completes the jet energy correction chain.

As a result of the calibration procedure, the energy scale is known to the percent level over a wide range of the available phase space (compare Figure 2) and as precise as 1% at 200 GeV for a central jet. A better understanding of the scale uncertainties allows many physics analyses to improve on their JEC-related systematic uncertainties in turn, allowing for more precise results in Standard Model measurements and Beyond the Standard Model searches.

All details on the 2010 calibrations have been published in JINST 6 P11002 and the 2011 calibrations are publicly available in CMS-DP-2012-006.

- Log in to post comments