Sometimes, everyday words are co-opted by scientists and used as technical terms. One of these is the word “berry”. Talking to a botanist friend of mine, I learned that tomatoes are berries, but strawberries are not — the scientific meaning of a berry has more to do with the reproductive structures of the plant than the way it tastes. The term “cross section” is a berry of particle physics — its technical meaning is very different from the common usage.

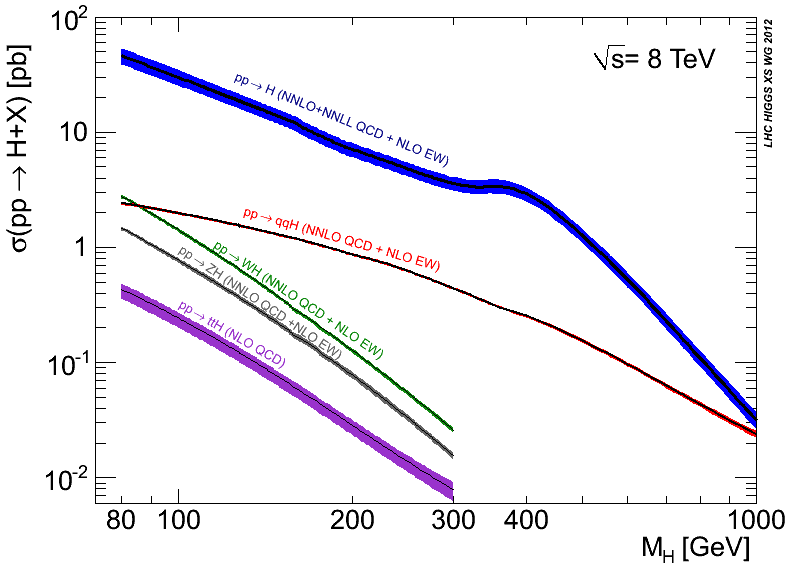

In everyday speech, “cross section” refers to a slice of an object. A particle physicist might use the word this way, but more often it is used to mean the probability that two particles will collide and react in a certain way. For instance, when CMS physicists measure the “proton-proton to top-antitop” cross section, they are counting how many top-antitop pairs were created when a given number of protons were fired at each other.

How did particle physicists come to use “cross section” in such a strange way? It’s a long story. In the early days of particle physics, particles were thought to be tiny indestructible balls. When marbles or billiard balls are rolled at each other, the probability that they will collide is proportional to the size of the balls, unless they are precisely aimed. Subatomic particles are so small that aiming individual particles at each other is out of the question — the best anyone can do is to shoot a lot of them in the same general area. The collision probability for a cloud of projectiles is simply the ratio of area covered by them to the total area of the cloud. When Xerxes darkened the sky with arrows at the Battle of Thermopylae, the probability of getting hit by an arrow was very high.

Early collision experiments were intended to measure the size of particles from their collision rate. Rutherford’s experiment, which collided alpha particles and gold nuclei in 1911, revealed that nuclei are much smaller than previously supposed. But soon, disparities arose: Neutrons are more likely to collide with certain nuclei when they are moving slowly than when they are fast. It is as though the neutrons change the area of their cross section mid-flight. Particles like neutrons are actually quantum clouds that pass through each other or interact with an energy-dependent probability — the likelihood of collision has little to do with a solid, cross-sectional area. Even though hard spheres is the wrong mental image, the term “cross section” stuck, and it’s common for a physicist to say, “this cross section depends on energy” when it would be nonsensical to imagine the size of the particle actually changing.

But why use “cross section” when alternatives like “probability” and “reaction rate” exist? Cross section is independent of the intensity and focus of the particle beams, so cross section numbers measured at one accelerator can be directly compared with numbers measured at another, regardless of how powerful the accelerators are. Arrows are arrows, no matter how many of them are fired into the sky.

This article originally appeared in Fermilab Today and has been reproduced with the permission of the author.

- Log in to post comments