CMS has recently conducted the largest deletion campaign in its history, deleting roughly 85 Petabytes (85’000’000’000’000’000 bytes) of data from the magnetic tapes, in order to free up space for the Run 3 collisions. No original raw data have been touched, meaning CMS can recreate any of the data needed.

The past months were exciting ones for the LHC in general and for CMS in particular: new proton collisions are being recorded by the experiments along the collider ring at an unprecedented collision energy and rate. Since the last LHC “Run”, which ended in 2018, the datasets that CMS recorded have been squeezed, wringed out, and turned on their head, in the quest of finally bringing the Standard Model to its breaking point – by finding evidence for new physics. In fact, each collision event has been re-analyzed a number of times with ever improved and refined reconstruction techniques, to maximize the precision with which we can describe the interesting physics happening in each proton collision.

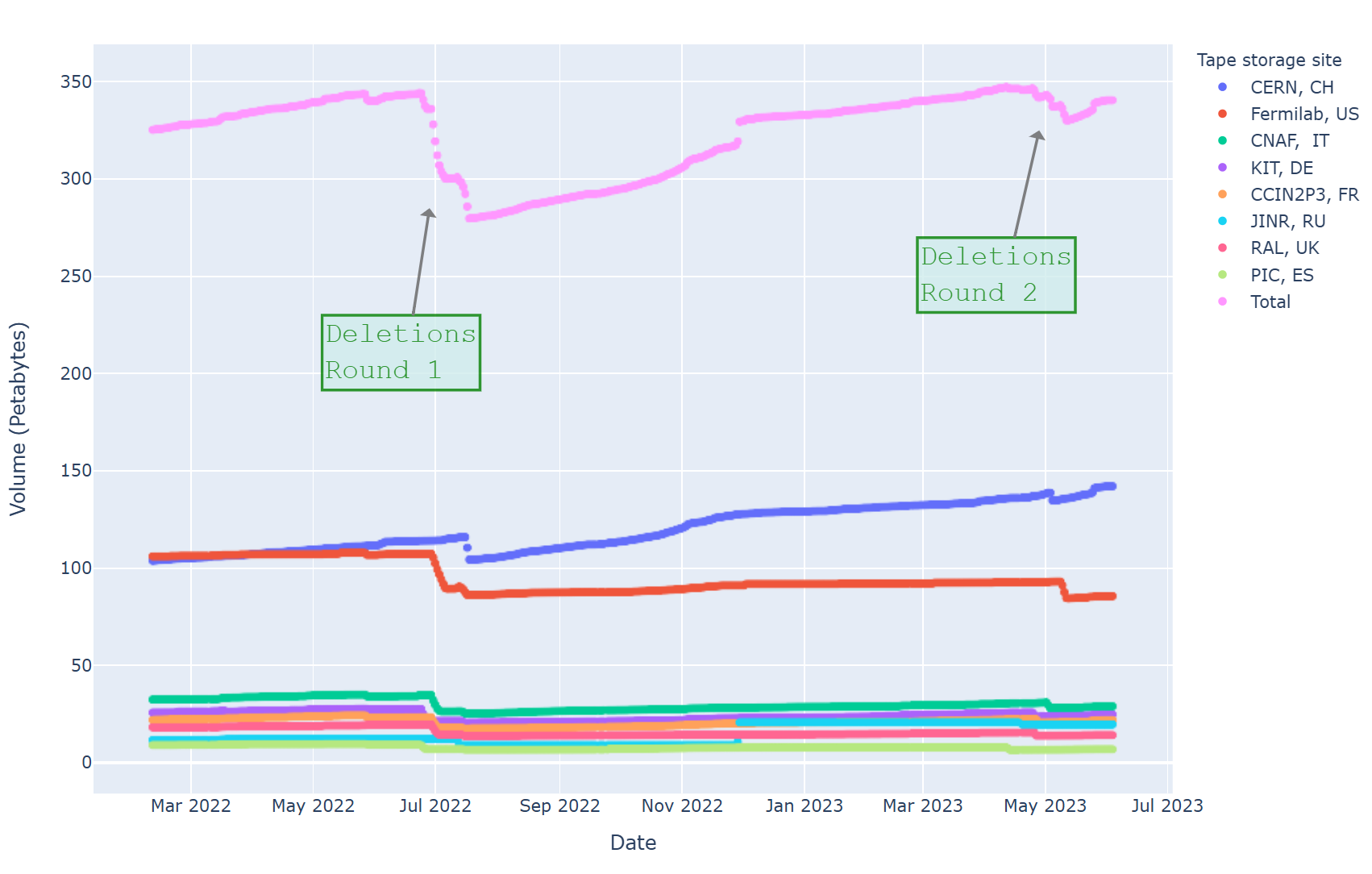

This means that there are different versions of each dataset available, corresponding to the different reconstruction algorithms used to turn the ones and zeros of the raw detector data into meaningful and interpretable objects like “muons”, “photons”, or “pions”, with which we perform the physics analyses. Adding the huge simulated samples that CMS uses to compare the data to the predictions of the Standard Model, we end up with a tremendous amount of information that can only be stored in large computing centers across the world, structured in the so-called Worldwide LHC Computing Grid (WLCG). In fact, there is so much data that the centers have to archive most of it on magnetic tapes (typically the older datasets), because there is simply not enough space available to keep everything on spinning disks or SSDs, which would provide a quicker turnaround time for reading the data. But what would happen if the tape systems were to get completely full and not accept any more data? Well, CMS would not be able to store any new collision data! To prevent this nightmare scenario, CMS has recently conducted the largest deletion campaign in its history, deleting roughly 85 Petabytes (85’000’000’000’000’000 bytes) of data from the magnetic tapes, in order to free up space for the Run 3 collisions. This means that roughly 25% of the data on tape has been deleted!

How much is a petabyte really? To picture a petabyte, think of a regular novel, picture the actual book. Now stack another on top of it, and another again and again until you have a stack as tall as a house. Keep going until the stack is as tall as a skyscraper, then the cruising altitude of an airplane, until you reach the international space station. But don’t stop there! Go all the way to the moon… go all the way to the moon 13 times and the data stored in those stacks of books is roughly one petabyte’s worth. Here, 85 petabytes were deleted - that’s over a thousand stacks of books all the way from the earth to the moon!

Figure 1: A magnetic tape cassette, installed at the CCIN2P3 computing center, in France.

The special thing about a deletion campaign of this magnitude is that it requires a concerted effort involving many different areas of the collaboration: the “Offline & Computing” area comes up with numbers about the current distribution of data across the Grid and with estimations for how much data needs to be deleted by the start of Run 3, to ensure a “smooth sailing” through the coming years. The “Physics Performance and Dataset” area, which checks and validates the data as ready to be used for analysis, provides insights into which datasets are outdated or superseded, and a list of datasets that can be deleted. Finally, the “Physics” area scrutinizes that list and potentially vetoes the deletion of certain data files, if they are still needed to complete ongoing studies. You can imagine the amount of interactions and grooming that we had to go through, to distill virtually millions of data files into a list of 85 PBs that could be deleted. Finally, it was time to involve the administrators of the computing centers in the WLCG to make sure that the actual deletion of the data from the tape drives could be safely executed. Many CMS researchers had to say goodbye to their favorite datasets. But it was a relatively easy goodbye, knowing that the datasets served us well in the past and were used for countless publications. Besides, we could in principle recreate the deleted datasets, given that we keep the original raw data (the ones and zeros coming straight from the detector read-out channels); we would never delete that precious information! CMS is now ready for the large amounts of data expected from Run 3, and time will tell if new physics phenomena are hiding in the past and future recorded collisions.

Figure 2: Time series plot of data on tape showing a drop in data volume on the days when the deletions were performed at the various computing centers.