Amongst all known elementary particles, the top quark is peculiar: weighing as much as a Tungsten atom, it completes the so-called 3rd generation of quarks and is the only quark whose properties can be directly measured. Owing to its mass, the top quark is unstable and, in CMS, decays much before it can interact with the proton remnants through the strong interaction and form hadrons (the bound states of quarks). It decays mostly to a W boson and a bottom (b) quark, and can therefore be identified from final states which involve the complete usage of the CMS detector; electrons, muons, jets, missing transverse energy — almost all particles or experimental signatures one can think of may be produced in top-quark events.

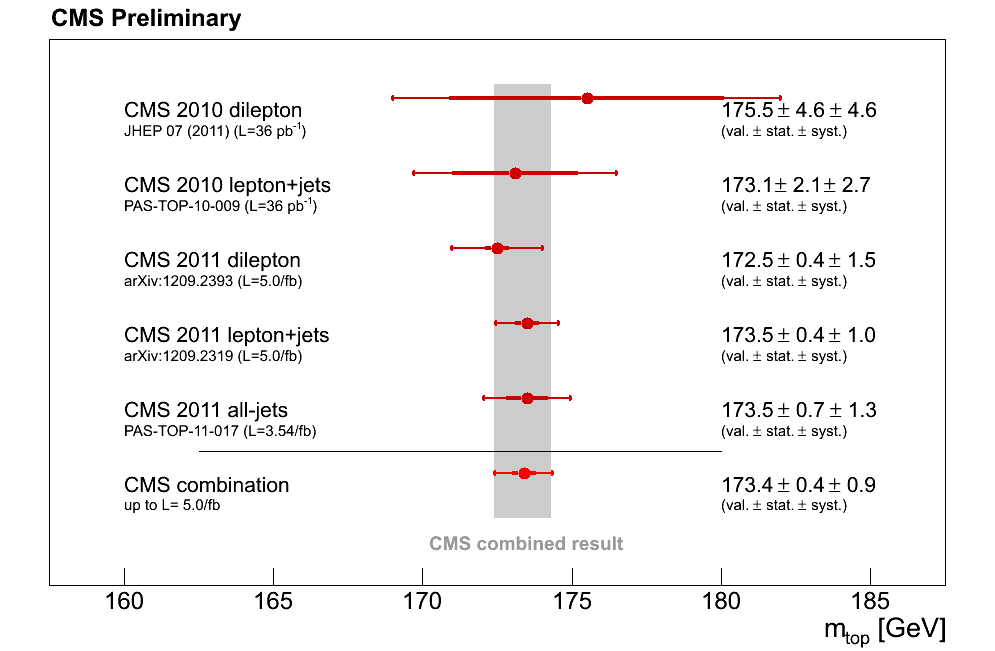

Since its discovery at the Tevatron at Fermilab, we have obtained a lot of knowledge about this particle and the characteristics of the collision events in which it is found. Some of the latest achievements include the discovery of the production of single top quarks in 2009 by CDF and by D0, the observation of an intriguing difference in the production of top quarks compared with their antiparticles as function of their rapidity (charge asymmetry) in 2011 (CDF and D0) and the grand combination of all the top-quark mass measurements performed by the Tevatron experiments in 2012. The combination has attained a remarkable precision of 0.54% making the top quark the quark with the most-accurately measured mass. To get to such a level of precision took almost 18 years of hard experimental work in order to understand the calibration of the detectors and to improve the data reconstruction techniques. From the theoretical point of view there was also substantial work made to describe better the physics of the top quark. It is therefore remarkable that it took only two years of data taking for the LHC, and in particular CMS, to achieve similar precision in the measurement of the top quark mass (Figure 1).

Part of the credit for this result goes to the “particle-flow” algorithm, which provides a global description of the events collected after each proton-proton collision. This algorithm makes the best use of the CMS Tracker to separate the charged particles from the neutral ones, and combines this information with the excellent resolution of the electromagnetic calorimeter (ECAL). The respective sub-detector elements (tracks and energy deposits) are “linked”, allowing the optimal measurement of the majority of the particles (~90%) that can be found in top-quark events. Most of these particles are found to be collimated and can be clustered in jets. Due to the reconstruction method used and careful calibration, the uncertainty in the determination of the energy scale of these jets is expected to be smaller than 2% in the region of interest for top-quark physics.

Credit must also be given to the extensive top-quark physics programme at the LHC in the last two years: a comprehensive review has been prepared by one of our previous top convenors. At CMS we have been focusing on the characterisation of the production of the top quarks singly, in pairs, and in association with other particles. These measurements can be directly compared with theoretical predictions and can also be used to verify if the main sources of theoretical uncertainty are reasonable. Almost all the possible final states that top-quark pairs can yield have been used to measure their production rate at both 7 TeV and 8 TeV. The most precise measurement (with a 4.2% uncertainty) is obtained from the di-lepton channel (where the two Ws decay into leptons) and it is mostly limited by the uncertainties in the jet energy scale, the branching ratio of the W boson to leptons and in the estimative of the irreducible background (single-top production in association with a W boson). The cross sections (or production rates) measured by the different channels at both these energies are found to be self-consistent and consistent with the theory predictions. Moreover, the current precision is starting to surpass the theoretical knowledge on the production rate of top-quark pairs. These results have already been used to infer theory parameters such as the “strength” of the strong couplings — i.e. the strong coupling constant (αS) — which is found to be in agreement with the current world average (Figure 2).

The production of single top quarks at the LHC also deserves to be highlighted — considerable progress has been made since the first results were obtained. The production rate for single tops depends on the Cabibbo-Kobayashi-Maskawa matrix element Vtb which determines by how much the charged electroweak interactions mix the top- and bottom-flavours of the quarks. The production of single top quarks has been established in two channels: the t-channel where the top quark is produced recoiling against a forward jet with high transverse momentum, and the tW-channel. A 9% uncertainty has been attained by CMS in the determination of the t-channel cross section at 7 TeV after the combination of three alternative analyses. The excellent result translates to a 4.8% uncertainty in the determination of Vtb and constitutes the most precise measurement of Vtb to date. The results found at 8 TeV and from the tW-channel analysis are found to be consistent. We are therefore getting closer to finding out experimentally if Vtb is indeed close to 1 — currently we can already state that |Vtb|>0.92 at 95% confidence level.

These and many other results have recently been presented at the 5th International Workshop on Top Quark Physics (TOP2012) held in Winchester, U.K. and in a CERN PH-LHC seminar. A few of these results have been highlighted here, but they barely do justice to the work of many people in the CMS top-quark group. For more on the top quark, you can consult the full collection of results from the CMS experiment. Niels Bohr famously said, “Physics concerns what we can say about Nature,” and these results allow us to make more accurate statements on the nature of the top quark as well as on the nature of the strong and electroweak interactions. With such precision achieved by CMS we can conclude that exciting times lie ahead for Top Physics — will we be able to identify subtle signs of new physics in the future?

— Submitted by Pedro Silva

- Log in to post comments