After an eight-week journey, the first HGCAL absorber structure (CE-H1) was delivered to CERN and is ready to be assembled, just 100 metres above where the detector will eventually be located.

Seventeen enormous boxes were delivered at the CMS experimental site at the beginning of November 2025, carrying a key component of the Hi-Lumi CMS detector: the first part of the structure of the new endcap calorimeters! CMS is constructed as a cylinder, with a central “barrel” part complemented by “endcaps” at either end. The 15m diameter endcaps are divided into four layers, or disks. The disk closest to the barrel holds the endcap calorimeters (that measure particle energies and trajectories) - 5m diameter 250 tonne “noses” that stick out from the disk. These calorimeter noses actually insert into the barrel when CMS is in its closed configuration. But they need to be replaced during Long Shutdown 3 (LS3 during which CMS will undergo a major upgrade) as the materials used in the existing calorimeters were not designed to withstand the radiation levels and cannot disentangle the multiple simultaneous collisions (up to 200) that the Hi-Lumi LHC will provide.

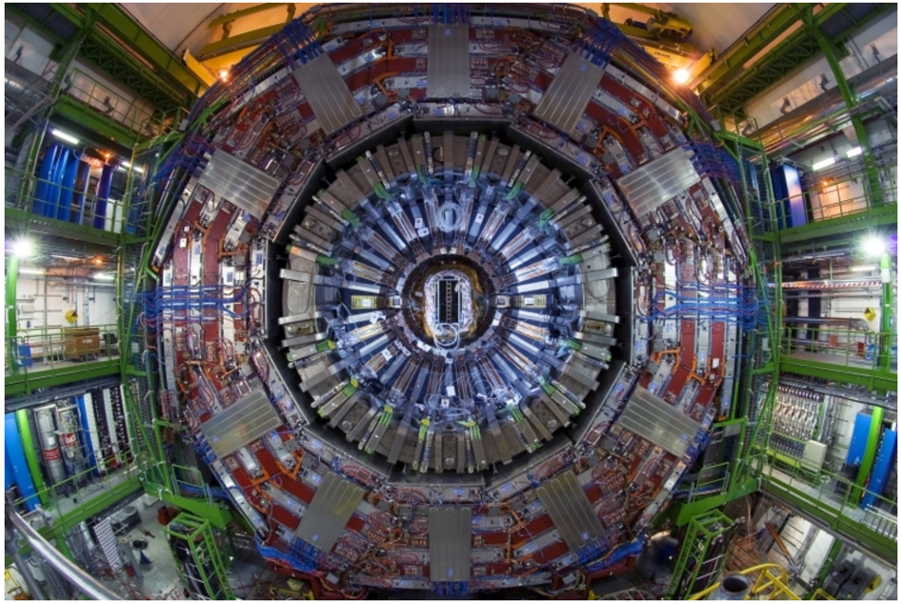

In the framework of this upgrade CMS is building a new “High Granularity Endcap Calorimeter” - HGCAL that will replace the existing endcap calorimeters. HGCAL comprises 47 layers of active elements (silicon modules in the regions of highest radiation, and plastic scintillator in the lower-radiation regions) interspersed with dense metal “absorber” structures. The first 26 layers (known as CE-E) will use a combination of lead, copper and tungsten as absorbers in a very compact set of self-supporting cassettes, whilst the following 21 layers (known as CE-H) will use stainless steel connected plates as the main absorber, with delicate detecting modules inserted in gaps between the plates. In 2029 the two new HGCAL endcaps, each weighing around 240 tonnes and containing more than 3 million detector elements, will be lowered 100m underground and connected to the endcap disks, ready for the High-Luminosity Run.

The CE-H1 (the name given to the first CE-H absorber structure) consists of a 100 mm thick 5.2m diameter steel backflange and its titanium supports (called 'wedges'), and 21 steel absorber disks (either 41.7mm or 60.7mm thick, up to 5.2m diameter) that stack up, creating the layers where the 252 hadronic cassettes (each covering 30 degrees of a layer) will be inserted. While Fermilab in the US is producing the hadronic cassettes, the manufacturing of the absorber structure was done in HMC-3 (Heavy Mechanical Complex 3) in Taxila, Pakistan, where a trial assembly was also performed. HMC-3 is part of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC), member institute of the CMS Collaboration. This was no ordinary metalwork; the machinery required high-precision to mill the plates to a flatness of less than 1mm. It took the team a painstaking six months to perfect the technique on the first three disks, which involved flipping the huge heavy plates over several times to relieve built-in stresses in the steel, followed by another full year dedicated to the demanding production of the remaining 19.

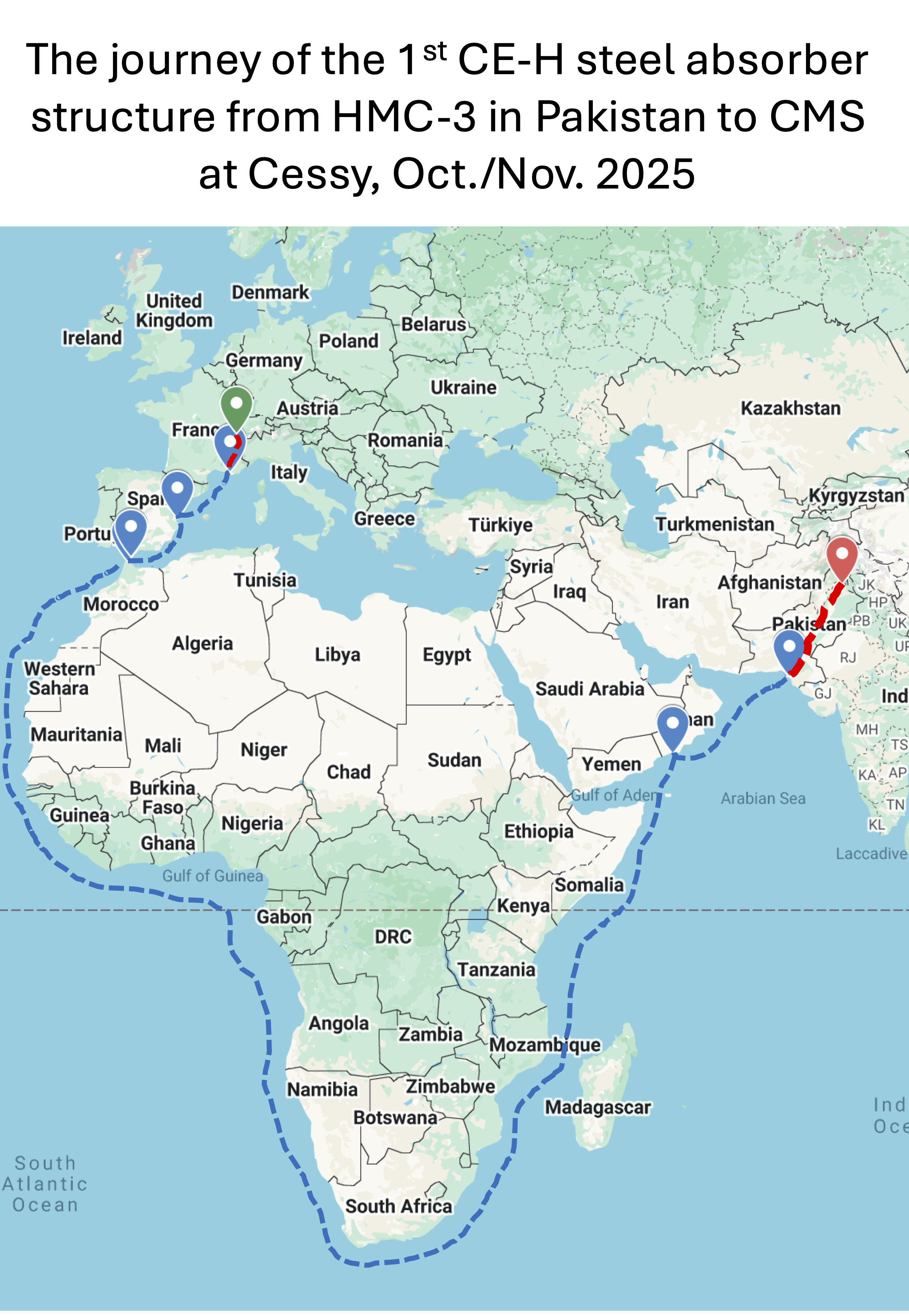

The long-awaited first CE-H absorber structure crossed three continents to make it to the CMS Assembly Hall in Cessy, France! Starting from Taxila, the pieces were loaded into many trucks to make their way to the port of Karachi, 1400km away. The pieces were then carefully distributed and loaded into eight shipping containers. These containers made their way by sea to Marseille in France, traveling around Africa and crossing the Strait of Gibraltar, and changing ships two times in various ports. From Marseille the boxes were again loaded onto trucks, ultimately arriving in Cessy, where a team of engineers from CERN and from PAEC were eagerly awaiting their arrival. Once the containers arrived at the CMS experiment and the team unboxed the components and checked that everything was in good condition, the next step was to start re-assembling the structure from the many large pieces. This process is going to continue until around March/April 2026, ensuring that the necessary tests are conducted before inserting the first fragile HGCAL cassettes.

ABOVE: the route taken to get the absorber structure to CERN. You can find this to download here.

While the logistical challenge, tackled with the help of Patrick Muffat of the CERN logistics group, of shipping the components across the globe was certainly non-trivial it pales in comparison to the complex undertaking of building and rigorously testing the absorber structure itself. Back in 2019, this part of the HGCAL project was just an idea sketched on a piece of paper by two senior CERN engineers - Stefano Moccia and Hubert Gerwig. After teaming up with younger CERN CMS engineers including Tom French and Karol Rapacz, and senior PAEC engineer Muhammad Shah, and many detailed calculations and simulations later, it was proven that this innovative structure would be suitable, and it was warmly supported by the CMS collaboration.

With substantial help from senior designer Marc Timmins, from the CERN Engineering department, the design was finalised with more than 200 production drawings produced. The next big challenge was the procurement under CERN responsibility of the stainless steel with low-magnetic permeability - necessary to avoid any possible movements of the structure when the 3.8T CMS solenoidal magnet was switched on. A French company, named InduSteel, undertook this project and provided the hundreds of tonnes of high quality raw steel, which was shipped to HMC-3. The small team of five engineers, supported by CERN graduates and students, joined forces with the team of engineers and technicians of PAEC at HMC-3. This grew to be a very fruitful collaboration over time, despite the distance and the time difference.

“The great thing is that in engineering it either works or it doesn’t – there is no grey area" as Stefano Moccia, the HGCAL Technical Coordinator (with Dave Barney) said when describing their collaboration. “In this case it worked extremely well!”.

ABOVE: Moment of truth: Watch the absorber being tested for the first time by the teams in Pakistanbefore being disassembled and shipped to CERN.

In March 2025, the build of the first of two new endcap structures (CE-H1) was completed, assembled layer by layer horizontally. However, when the endcap is to be connected to the CMS detector, this structure will be in a vertical position, which meant one thing: it was time to swivel it! The absorber assembly was rotated by 90 degrees using two pins fixed to the absorber plates as the pivot axis. It was then lowered onto a lower support foot, in order to transfer the entire weight of 170 tons via only the backflange to this support.The assembly was then stabilized by tie-rods connected to the backflange, so that the whole structure was held in a cantilevered condition. This configuration represented the load condition most similar to the final CMS setup. Once it had its final orientation, the Pakistani team could measure the possible deformation and cross-check with the expected finite element analysis (FEA) calculations. The test was carried out with success in Taxila, meaning that the CE-H1 structure could be rotated back to the horizontal, disassembled and shipped to CERN.

Moving forwards with the confidence of the successful assembly and tests, the next months at CERN will be busy, but leading to an extremely rewarding result. The next steps, presented in the animation below, will include inserting the hadronic cassettes, attaching the electromagnetic part of the HGCAL detector (CE-E), installing thermal screen panels, and cooling it down to −35° Celsius with a sophisticated CO2 cooling system, before finally rotating it into a vertical position with a dedicated tooling similarly as it was done in Pakistan. This was only the beginning, so hold on—there is so much more to come!