Dark matter is mysterious. In some ways, we know a lot about it, including its average density in the universe and upper limits for how strongly the dark matter particles might interact with each other or with “normal” Standard Model particles. In other ways, however, we haven’t even scratched the surface of the “dark world”. In particular, we don’t know what kind of particle(s) makes up all of the dark matter whose gravitational effects are clearly seen across the universe. The strategy, therefore, is to make the net we cast as wide as possible, in the hope of catching an elusive sign of those subatomic dark matter particles.

CMS physicists recently completed the first search, at the LHC, in the context of the inelastic dark matter model (iDM). In this model (a well-motivated guess for what dark matter might be), a dark matter particle can be produced in a proton-proton (pp) collision, travel some distance in our detector, and eventually decay into a pair of muons, which are heavier cousins of the electron. Three distinct features in the iDM model help us to separate such a dark matter signal from look-alike Standard Model processes (“background”).

The missing transverse momentum: In an LHC pp collision, the two protons hit each other head-on, with zero net transverse momentum. Therefore, conservation of momentum (as taught in introductory physics classes) implies that there must be zero net transverse momentum after the collision. If we add up the momenta of all the particles that we observe and it does not add up to zero, then we have a good sign that something else (dark matter, hopefully) was produced and carried away the “missing” momentum.

A displaced dimuon vertex: One of the new particles predicted by the iDM model is “long-lived”, meaning that it can survive long enough to travel relatively far in our detector, before decaying into the two muons. This means that the origin of the muon tracks will be “displaced” with respect to the pp collision point, looking as if they popped out of thin air!

Close-by muon tracks: Even though “muon” is literally the middle name of the Compact Muon Solenoid experiment, finding the two muons emitted by iDM particles is challenging, because they are expected to be very close to each other (nearly overlapping) and have relatively low energies. On the other hand, these features make them different from most other collisions (“events”) with muons.

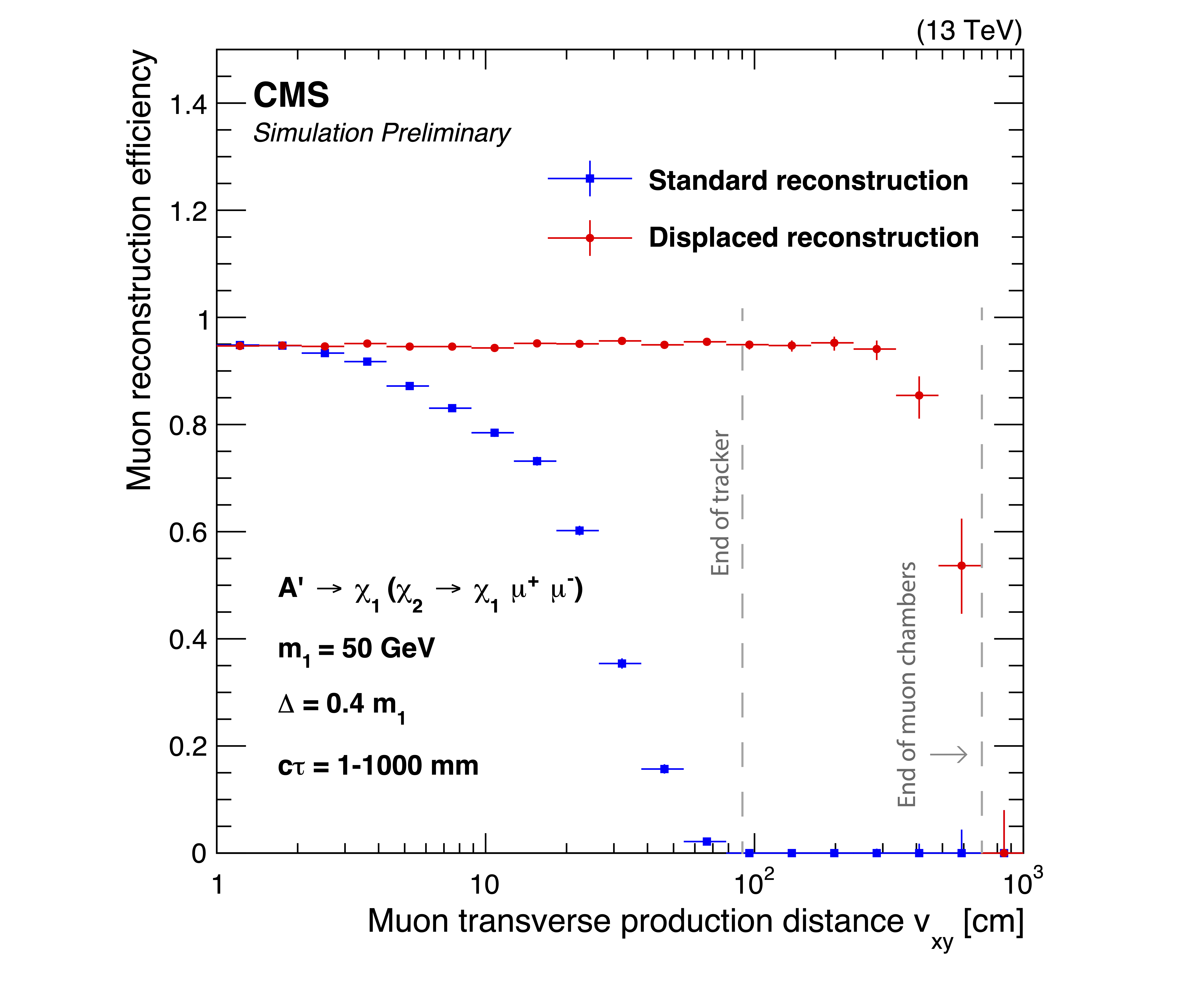

To maximize our ability to find displaced muons, we followed a strategy similar to that used by a previous CMS analysis. Using complementary information from the silicon tracker (the innermost detector of CMS) and the muon system (the outermost detectors), we can look for muons with a wide range of displacements (distance between the dimuon vertex and the pp collision point), as shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The efficiency of the “displaced reconstruction” algorithm (red) is much better than that of the standard reconstruction (blue), so that dimuons from long-lived dark matter particles can be identified much better, especially if produced between the external radii of the tracker and of the muon detectors (dashed gray lines).

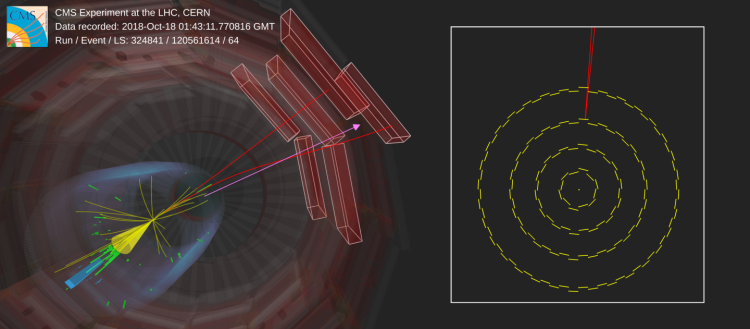

As illustrated by the event display shown in Fig. 2, the iDM features are so distinct that, out of the billions of proton-proton collisions recorded by CMS, less than 4 events are expected to survive these “selection criteria”. This event is also shown in the header image. In the transverse view (right), it is clear that the muons were produced some distance away from the center of the detector.

Figure 2: Event display showing an iDM candidate with two muons (red) and missing transverse momentum (purple). You can play with the event display also here in a separate page.

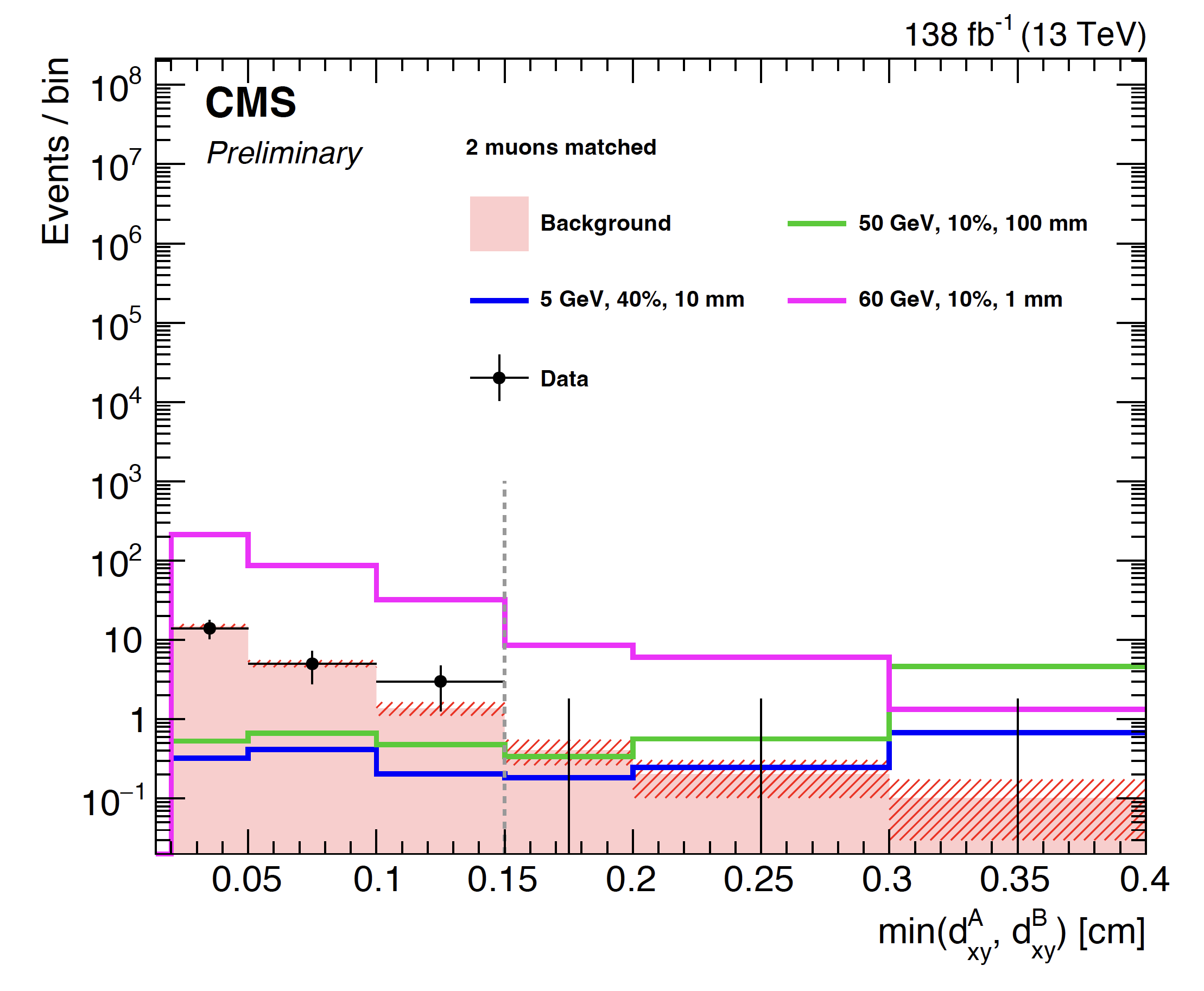

Figure 3 shows that the measured muon displacement distribution agrees very well with the “background” expected from Standard Model events. This means that we do not see any evidence that elusive dark matter particles contribute to the observed events. In other words, our net came up empty this time, despite having been optimized over several years to be as sensitive as possible to the iDM particles. The good news is that there are many more kinds of fish in the theoretical sea, and many other ideas for how to snare dark matter in the CMS detector! Stay tuned to the next episodes.

Figure 3: The measured muon displacement distribution (black circles) agrees well with the “background” Standard Model expectation (red histogram, with the dashed region showing the uncertainty), meaning that we do not see any signal of dark matter particles (represented by the magenta, green, and blue lines for three different iDM scenarios).

Read more about these results:

-

CMS Physics Analysis Summary "Search for inelastic dark matter in events with two displaced muons and missing transverse momentum in proton-proton collisions at 13 TeV"

-

@CMSExperiment on social media: facebook - twitter - instagram

- Do you like these briefings and want to get an email notification when there is a new one? Subscribe here